Artist:

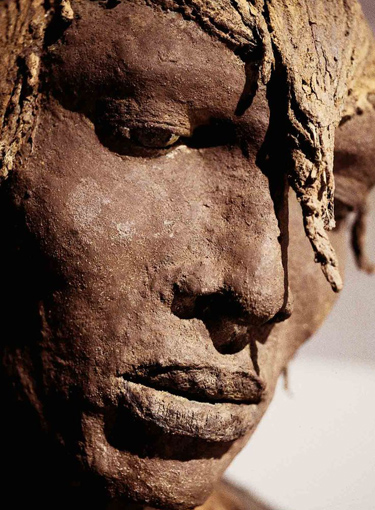

Ousmane Sow

Title:

Massai Warrior on the Watch

Year:

1989

Adress:

Massai Warrior on the Watch

Website:

www.maisonousmanesow.com:

The Masai are nomadic herdsmen living in the south of Kenya and the north of Tanzania. They remain one of the few warrior tribes of Africa that have not renounced their traditions. Estimated at three hundred thousand at the end of the 60s, the group is now in process of integration as they increasingly settle in the towns.

In 1989, Ousmane Sow took a passionate interest in this flamboyant African tribe with its customs being eradicated by schooling, conversion to Christianity and permanent settlement. They are famed for their elegance and their daring, displayed in particular during ancestral initiation rites.

Young Masai from fourteen to thirty are called “moran” [warrior] and wear their hair in decorative braids.

www.africanah.org:

Inspired by Riefenstahl’s photos of the Nuba, he abandoned his career as a physiotherapist, invented new techniques and materials, and created The Nuba, a group of muscular, virile, larger-than-life wrestlers (1984-87). Monl representations of The Masai (1989) and The Zulus (1990) followed, and in 1992 his work was selected for Documenta IX. Turning to global narrative, he produced a massive tableau of The Battle of Little Big Horn (1998).

Audacious in size, Sow’s figures are modelled with proportional volume and anatomical detail, creating energy in frozen movement and strong human presence. The powerful physicality of 68 of his figures exhibited on the Pont des Arts in Paris (1999), astonished the world and led to commissions from the International Olympic Committee and the Medecins du Monde. Coming from a vacuum of representation of the African body and raising anxious ghosts of racism, Sow’s sculptures boldly confront stereotypes, representing the body without qualms. They carry a message of tolerance and humanity.

www-parismatch-com:

Figure de l'art africain contemporain, le sculpteur sénégalais Ousmane Sow est mort tôt jeudi à Dakar à l'âge de 81 ans, a annoncé sa famill"Il emporte avec lui rêves et projets que son organisme trop fatigué n'a pas voulu suiv", a souligné sa famille, précisant qu'il avait fait ces derniers mois plusieurs séjours à l'hôpital à Paris et à Dakar.

Ousmane Sow Introduit À L'Académie Des Beaux arts Par François Hollande, Lors D’un Cérémonie À L’Elysée En Décembre 2013 2.

Translate

Figure of contemporary African art, Senegalese sculptor Ousmane Sow died early Thursday in Dakar at the age of 81, hi"He takes with him dreams and projects that his too tired body did not want to follow," said his family, adding that he had made several hospital stays in Paris and Dakar in recent months.

Ousmane Sow Introduced To The Academy Of Fine Arts By François Hollande, During A Ceremony At The Elysee Palace In December 2013 2.

www.aisonousmanesow.com:

Amongst this threatened race in South Sudan, where the men go naked, wrestling matches are seen as a ritual that lifts the soul. After the fights, men and women choose their partners. Nouba women practice tattooing and scarification for religious, ethnic and aesthetic purposes.

Ousmane Sow: 'As far back as I can remember, I have always sculpted. I never thought of making a profession of it, until the day I left deeply moved by the photographs of Leni Riefenstahl portraying the Nouba of Kau.What interested me about the nouba wrestlers is that they care of their bodies and that, at some point in their lives, they run the risk of being disfigured.'

www.ousmanesow.com: As if driven to return to the very source, to the origins an development of African art, Ousmane Sow's work might well appear to be a contemporary digest, an exaggerated vision of a long forgotten history. Following the example of the first ancient and classical art of the African continent - the large, terracotta figurative statues of the Nok culture of Nigeria, as mute and as hallucinated as the Easter Island statues - Ousmane Sow began by kneading the earth. A new creative force seeking to build up an improbable army of the shadows, Sow raised his Golem warriors by perfecting an alchemist's mixture of his own concoction. His esthetic of secrecy corresponded exactly with his esthetic of initiation.

How can you think of reproduction when you are striving to produce? Transmutation into bronze - completely hypothetical at that moment - would have been considered as a vulgar and flashy transformation of clay into gold.

It's a mistake to attribute to primary works of art an originality that cannot be reproduced.

We know that as early as the 11th century the ancient Ife civilization in the Yoruba lands, in the south-west of modern Nigeria had discovered how to cast, having already achieved remarkable mastery of terracotta modeling.

But the experiment would have soon ended if the artist had not discovered, first with fascination, then astonishment and emotion, a regeneration and a real metamorphosis in his work. As we know, in the end replicants always escape from their creator…

For his first three bronzes, Ousmane Sow immediately turned to his earliest works: Dancer with Short Hair and the Standing Wrestler from the Nuba series, an"Mother and Child" from the Masai series. Perhaps the most brutal, in any case the most nude and undeniably the most alive, even though they remain imbued with a sense of moderation, restraint and self control that we associate with the Yoruba and the Fulani.

In the remote Kordofan region, in the south of Sudan, where the Nuba survive and still live, young virgins dance the myertum, the "dance of love". They move closer and closer to the victorious wrestlers, who sit in a circle their eyes lowered, after the annual ceremonial combat. They smear their bodies with black or red earth to make them more athletic and desirable. Only bronze, with its dark, shimmering patina, could recreate the initial erotic gleam of the Dancer with Short Hair, her oblique, hollowed highlights, her supple, animal power. With the Standing Wrestler the bronze makes him stronger, stockier, more concentrated, more violent. He's certainly less human, standing there, one solid block, like a god, a force in motion. The mask he has skillfully painted on his face to frighten his opponents - here etched in green acid in the very flesh of the bronze - acquires a virulence that is closer to actual Nuba war paint, made from charcoal dust and crushed shell.

Contrary to the original human creations, they demand a resurrection of the flesh, a touch of eternity as opposed to a rotting straw...

And the mother breastfeeding her child with her dress and clothing melting into the flesh is here transformed into Maternity. Emerging like a lotus flower from the folds of clothing, colored warm ochre by nitrates, the young woman's head, shaven, smooth and burnt dark by the sun, takes on a Buddha-like grace. Her feet, however, deformed as in Picasso's cubist manner, coarsely hacked as Baselitz might have done, remind us in an immediate, clear and perceptible fashion of the wounds and shocks that African feet suffer from their endless walking.

Ousmane Sow is certainly not the first to color his bronzes. Giacometti and Germaine Richter experimented with it before him, but as a game, a fad, a whim, rarely out of necessity. For the Senegalese, Sow, bronze is inconceivable without color, which is its mask, its interior adornment.

With Ousmane Sow, it's the Africa of bronze and gold, proud and heroic, that comes to life under a beating sun.

Text: Emmanuel Daydé

www.mollyakshinhat.ca:

They are giants. Somehow related to the clay scultures that came to life in the Sinbad movies made in the fifties or sixties, Ousmane Sow's twenty something figurative works feel like they just sprang out of the ground onto the low grey wood just outside the National Gallery of Canada. Capturing scenes from what was once(?) or still is the daily life of three of Africa's tribes—the Peulh (1993-1994), the Nouba (1984-1987) and the Massaï (1988-1989)—Sow uses an alchemy, a medium designed by himself to create his figures. Larger than life, the sometimes over two metre high figures, with rippling muscles indicative of the harshness of life lived traditionally by these peoples, Sow destroys an entire set of stereotypes through their faces. The size and strength of the figures would easily lead viewers to expect some kind of violence or dominance to show in the figures' faces. But contrary to what our culture (at least) conditions us to believe, the faces of Sow's figures are calm, contemplative, thoughtful. Perhaps the most surprising of these (for me) isding Warrior (one of the Massaï). At least nine feet high, the warrior stands with arms apart carrying a tall shield and a spear in each hand wearing only a loincloth. He literally stretches up over most viewers, and with his elongated ears and head tilted forward, he quietly looks at the ground. After looking at his remarkable body, his face comes as an extraordinary window into the mysteries of what this warrior's thoughts might be and the landscape he is confronting. (By the way, I did see more than a few women and gay men(?), chuckling or smiling as they looked at Sow's work.) Sow's training as a physiologist shows in every inch of these deceptively simple yet incredibly detailed and complex works. To represent figures of such scale well in such a wide variety of positions and postures, doing everything from participating in scarification ceremonies, wrestling, sacrificing animals, breastfeeding, and drumming for instance, requires an expansive knowledge of the human body and how it works. If not that, ten at least many many many hours of close observation of the human form. Sow's medical knowledge clearly plays a dramatic role in his sculpture technique. Sometimes it is possible to see the network of gauze below the layers of clay or plaster or mud that Sow has used. Although most of the works are of varying tones of dark clay and brown, the most recent series (The Peuhl) also uses a dull almost verdigris shade of green. In 1999, Sow held two extraordinary exhibitions of a series of works on the subject of the Battle of Little Big Horn. Consisting of twenty-three figures, in Paris the works were shown moving across a bridge. In Africa, the sculptures were shown in Dakar (Senegal) at the site of the Gorée Memorial (Gorée island is notorious for its use as a holding cell for millions of Africans sold into the Atlantic slave trade.) Born in 1935, Sow held his first exhibition at the age of fifty. He joins the small but internationally renowned group of Senegalese artists, known primarily for their brillian in storytelling and visualization. Filmmaker Idrissa Ouedraogo and writer and filmmaker Sembene Ousmane for instance. Using non-professional actors and members of his extended family, Ouedraogo made the internationally acclaimed films Yaaba and Tilaii. Xala(The Curse, 1974) is perhaps Sembene Ousmane's most famous film. (It and other African films are available at Invisible Cinema, 319 Lisgar, 237-0769). Sow's work stands as a testament to the starkness of lives carved out by what we may see as harsh daily work, but the work is also witness to human lives not quite robbed of the symbolic and the meaningful ritual, and face-to-face human interaction. www.wikipedia.org:

Ousmane Sow (10 October 1935 – 1 December 2016) was a Senegalese sculptor of larger-than-life statues of people and groups of people.

ow was born in Dakar, Senegal, on 10 October 1935. After the death of his father in 1956, he left Dakar to study in France, where he obtained a diploma in physiotherapy. He returned to Senegal after ibecame independent in 1960 and started a practice in physiotherapy. He later went back to France and practised there, but returned to Senegal in 1978. He died in Dakar on 1 December 2016 at the age of 81.

Sow was inspired by photographs by Leni Riefenstahl of the Nuba peoples of southern Sudan, and from 1984 began to work on a series of larger-than-life sculptures of muscular Nuba wrestlers. To make them, he developed a series of new techniques and materials. They were shown at the Centre Culturel Français de Dakar in 1987. Sow later made series of sculptures of Maasai people, of Zulu people, of Peul or Fulani people, and, in the late 1990s, of Native Americans.

www.rbb85.wordpress.com:

In 2008 Sow was honored with a Prince Claus Award from the Netherlands in the theme Culture and the human body.

www.maisonousmanesow.com:

The Maison Ousmane Sow has been visited by many people since its opening on May 5th, 2018. In order to create his sculptures, for long hours, Ousmane Sow remaied locked in his studio house in Dakar, a place where he lived from 1999 until the end of his life. This house, in itself is a work of art. Its floor is still covered with tiles made by the artist himself and the walls remain painted with "his material". Definitely contemporary, this building now shelters about thirty original pieces of artwork.

The Masai are nomadic herdsmen living in the south of Kenya and the north of Tanzania. They remain one of the few warrior tribes of Africa that have not renounced their traditions. Estimated at three hundred thousand at the end of the 60s, the group is now in process of integration as they increasingly settle in the towns.

In 1989, Ousmane Sow took a passionate interest in this flamboyant African tribe with its customs being eradicated by schooling, conversion to Christianity and permanent settlement. They are famed for their elegance and their daring, displayed in particular during ancestral initiation rites.

Young Masai from fourteen to thirty are called “moran” [warrior] and wear their hair in decorative braids.

www.africanah.org:

Inspired by Riefenstahl’s photos of the Nuba, he abandoned his career as a physiotherapist, invented new techniques and materials, and created The Nuba, a group of muscular, virile, larger-than-life wrestlers (1984-87). Monl representations of The Masai (1989) and The Zulus (1990) followed, and in 1992 his work was selected for Documenta IX. Turning to global narrative, he produced a massive tableau of The Battle of Little Big Horn (1998).

Audacious in size, Sow’s figures are modelled with proportional volume and anatomical detail, creating energy in frozen movement and strong human presence. The powerful physicality of 68 of his figures exhibited on the Pont des Arts in Paris (1999), astonished the world and led to commissions from the International Olympic Committee and the Medecins du Monde. Coming from a vacuum of representation of the African body and raising anxious ghosts of racism, Sow’s sculptures boldly confront stereotypes, representing the body without qualms. They carry a message of tolerance and humanity.

www-parismatch-com:

Figure de l'art africain contemporain, le sculpteur sénégalais Ousmane Sow est mort tôt jeudi à Dakar à l'âge de 81 ans, a annoncé sa famill"Il emporte avec lui rêves et projets que son organisme trop fatigué n'a pas voulu suiv", a souligné sa famille, précisant qu'il avait fait ces derniers mois plusieurs séjours à l'hôpital à Paris et à Dakar.

Ousmane Sow Introduit À L'Académie Des Beaux arts Par François Hollande, Lors D’un Cérémonie À L’Elysée En Décembre 2013 2.

Translate

Figure of contemporary African art, Senegalese sculptor Ousmane Sow died early Thursday in Dakar at the age of 81, hi"He takes with him dreams and projects that his too tired body did not want to follow," said his family, adding that he had made several hospital stays in Paris and Dakar in recent months.

Ousmane Sow Introduced To The Academy Of Fine Arts By François Hollande, During A Ceremony At The Elysee Palace In December 2013 2.

www.aisonousmanesow.com:

Amongst this threatened race in South Sudan, where the men go naked, wrestling matches are seen as a ritual that lifts the soul. After the fights, men and women choose their partners. Nouba women practice tattooing and scarification for religious, ethnic and aesthetic purposes.

Ousmane Sow: 'As far back as I can remember, I have always sculpted. I never thought of making a profession of it, until the day I left deeply moved by the photographs of Leni Riefenstahl portraying the Nouba of Kau.What interested me about the nouba wrestlers is that they care of their bodies and that, at some point in their lives, they run the risk of being disfigured.'

www.ousmanesow.com: As if driven to return to the very source, to the origins an development of African art, Ousmane Sow's work might well appear to be a contemporary digest, an exaggerated vision of a long forgotten history. Following the example of the first ancient and classical art of the African continent - the large, terracotta figurative statues of the Nok culture of Nigeria, as mute and as hallucinated as the Easter Island statues - Ousmane Sow began by kneading the earth. A new creative force seeking to build up an improbable army of the shadows, Sow raised his Golem warriors by perfecting an alchemist's mixture of his own concoction. His esthetic of secrecy corresponded exactly with his esthetic of initiation.

How can you think of reproduction when you are striving to produce? Transmutation into bronze - completely hypothetical at that moment - would have been considered as a vulgar and flashy transformation of clay into gold.

It's a mistake to attribute to primary works of art an originality that cannot be reproduced.

We know that as early as the 11th century the ancient Ife civilization in the Yoruba lands, in the south-west of modern Nigeria had discovered how to cast, having already achieved remarkable mastery of terracotta modeling.

But the experiment would have soon ended if the artist had not discovered, first with fascination, then astonishment and emotion, a regeneration and a real metamorphosis in his work. As we know, in the end replicants always escape from their creator…

For his first three bronzes, Ousmane Sow immediately turned to his earliest works: Dancer with Short Hair and the Standing Wrestler from the Nuba series, an"Mother and Child" from the Masai series. Perhaps the most brutal, in any case the most nude and undeniably the most alive, even though they remain imbued with a sense of moderation, restraint and self control that we associate with the Yoruba and the Fulani.

In the remote Kordofan region, in the south of Sudan, where the Nuba survive and still live, young virgins dance the myertum, the "dance of love". They move closer and closer to the victorious wrestlers, who sit in a circle their eyes lowered, after the annual ceremonial combat. They smear their bodies with black or red earth to make them more athletic and desirable. Only bronze, with its dark, shimmering patina, could recreate the initial erotic gleam of the Dancer with Short Hair, her oblique, hollowed highlights, her supple, animal power. With the Standing Wrestler the bronze makes him stronger, stockier, more concentrated, more violent. He's certainly less human, standing there, one solid block, like a god, a force in motion. The mask he has skillfully painted on his face to frighten his opponents - here etched in green acid in the very flesh of the bronze - acquires a virulence that is closer to actual Nuba war paint, made from charcoal dust and crushed shell.

Contrary to the original human creations, they demand a resurrection of the flesh, a touch of eternity as opposed to a rotting straw...

And the mother breastfeeding her child with her dress and clothing melting into the flesh is here transformed into Maternity. Emerging like a lotus flower from the folds of clothing, colored warm ochre by nitrates, the young woman's head, shaven, smooth and burnt dark by the sun, takes on a Buddha-like grace. Her feet, however, deformed as in Picasso's cubist manner, coarsely hacked as Baselitz might have done, remind us in an immediate, clear and perceptible fashion of the wounds and shocks that African feet suffer from their endless walking.

Ousmane Sow is certainly not the first to color his bronzes. Giacometti and Germaine Richter experimented with it before him, but as a game, a fad, a whim, rarely out of necessity. For the Senegalese, Sow, bronze is inconceivable without color, which is its mask, its interior adornment.

With Ousmane Sow, it's the Africa of bronze and gold, proud and heroic, that comes to life under a beating sun.

Text: Emmanuel Daydé

www.mollyakshinhat.ca:

They are giants. Somehow related to the clay scultures that came to life in the Sinbad movies made in the fifties or sixties, Ousmane Sow's twenty something figurative works feel like they just sprang out of the ground onto the low grey wood just outside the National Gallery of Canada. Capturing scenes from what was once(?) or still is the daily life of three of Africa's tribes—the Peulh (1993-1994), the Nouba (1984-1987) and the Massaï (1988-1989)—Sow uses an alchemy, a medium designed by himself to create his figures. Larger than life, the sometimes over two metre high figures, with rippling muscles indicative of the harshness of life lived traditionally by these peoples, Sow destroys an entire set of stereotypes through their faces. The size and strength of the figures would easily lead viewers to expect some kind of violence or dominance to show in the figures' faces. But contrary to what our culture (at least) conditions us to believe, the faces of Sow's figures are calm, contemplative, thoughtful. Perhaps the most surprising of these (for me) isding Warrior (one of the Massaï). At least nine feet high, the warrior stands with arms apart carrying a tall shield and a spear in each hand wearing only a loincloth. He literally stretches up over most viewers, and with his elongated ears and head tilted forward, he quietly looks at the ground. After looking at his remarkable body, his face comes as an extraordinary window into the mysteries of what this warrior's thoughts might be and the landscape he is confronting. (By the way, I did see more than a few women and gay men(?), chuckling or smiling as they looked at Sow's work.) Sow's training as a physiologist shows in every inch of these deceptively simple yet incredibly detailed and complex works. To represent figures of such scale well in such a wide variety of positions and postures, doing everything from participating in scarification ceremonies, wrestling, sacrificing animals, breastfeeding, and drumming for instance, requires an expansive knowledge of the human body and how it works. If not that, ten at least many many many hours of close observation of the human form. Sow's medical knowledge clearly plays a dramatic role in his sculpture technique. Sometimes it is possible to see the network of gauze below the layers of clay or plaster or mud that Sow has used. Although most of the works are of varying tones of dark clay and brown, the most recent series (The Peuhl) also uses a dull almost verdigris shade of green. In 1999, Sow held two extraordinary exhibitions of a series of works on the subject of the Battle of Little Big Horn. Consisting of twenty-three figures, in Paris the works were shown moving across a bridge. In Africa, the sculptures were shown in Dakar (Senegal) at the site of the Gorée Memorial (Gorée island is notorious for its use as a holding cell for millions of Africans sold into the Atlantic slave trade.) Born in 1935, Sow held his first exhibition at the age of fifty. He joins the small but internationally renowned group of Senegalese artists, known primarily for their brillian in storytelling and visualization. Filmmaker Idrissa Ouedraogo and writer and filmmaker Sembene Ousmane for instance. Using non-professional actors and members of his extended family, Ouedraogo made the internationally acclaimed films Yaaba and Tilaii. Xala(The Curse, 1974) is perhaps Sembene Ousmane's most famous film. (It and other African films are available at Invisible Cinema, 319 Lisgar, 237-0769). Sow's work stands as a testament to the starkness of lives carved out by what we may see as harsh daily work, but the work is also witness to human lives not quite robbed of the symbolic and the meaningful ritual, and face-to-face human interaction. www.wikipedia.org:

Ousmane Sow (10 October 1935 – 1 December 2016) was a Senegalese sculptor of larger-than-life statues of people and groups of people.

ow was born in Dakar, Senegal, on 10 October 1935. After the death of his father in 1956, he left Dakar to study in France, where he obtained a diploma in physiotherapy. He returned to Senegal after ibecame independent in 1960 and started a practice in physiotherapy. He later went back to France and practised there, but returned to Senegal in 1978. He died in Dakar on 1 December 2016 at the age of 81.

Sow was inspired by photographs by Leni Riefenstahl of the Nuba peoples of southern Sudan, and from 1984 began to work on a series of larger-than-life sculptures of muscular Nuba wrestlers. To make them, he developed a series of new techniques and materials. They were shown at the Centre Culturel Français de Dakar in 1987. Sow later made series of sculptures of Maasai people, of Zulu people, of Peul or Fulani people, and, in the late 1990s, of Native Americans.

www.rbb85.wordpress.com:

In 2008 Sow was honored with a Prince Claus Award from the Netherlands in the theme Culture and the human body.

www.maisonousmanesow.com:

The Maison Ousmane Sow has been visited by many people since its opening on May 5th, 2018. In order to create his sculptures, for long hours, Ousmane Sow remaied locked in his studio house in Dakar, a place where he lived from 1999 until the end of his life. This house, in itself is a work of art. Its floor is still covered with tiles made by the artist himself and the walls remain painted with "his material". Definitely contemporary, this building now shelters about thirty original pieces of artwork.